Nothing New Under the Sun: My West Feliciana Parish Family’s confrontation with Voter Suppression

Ecclesiastes 1:9 – “What has been will be again, what has been done will be done again; there is nothing new under the sun.”

In recent months, we’ve seen an uptick in votersuppression tactics that make Americans question whether their civil liberties are under attack. However, the right to vote for African Americans has always been a source of contention for the American majority. For us, there is nothing new under the sun.

I offer the article entitled “In a Word: The Racist Origins of ‘Bulldozer’” by Andy Hollandbeck of the Saturday Evening Post as highly recommended reading material. Hollandbeck provides the historical origins of the word (originally “bulldoser”) meaning “a dose of the bull(whip).” Bulldozing was one of many forms of physical violence used to enforce voter suppression against formerly enslaved black people. He recounts the events surrounding the Election of 1876, an important election that would shape the South for generations. The two Presidential candidates: Republican, Rutherford B. Hayes and Democrat, Samuel Tilden.

The Civil War, which ended in defeat for the South in 1865 ushered in the era of Reconstruction in which the newly freed African slaves who overwhelmingly registered Republican, would be granted, first, their humanity, and second, full U.S. citizenship and all rights associated with it. One of those rights included the right to vote—the most powerful tool available to them to reshape their lives and future, both politically and economically. That right posed great threat to the Southern Confederate Democrat. They felt that the Federal Government, who recently re-admitted them to the union, was infringing on their long-standing establishment by overtaxing them and crippling their communities economically. Hollandbeck describes the outcome of this disputed election:

Going into the election, in five states — Alabama, Florida, Louisiana, Mississippi, and South Carolina — a majority of registered voters were African American. One would expect, in a fair election, that the Republican candidate would easily take these states. But after the votes were tallied, Tilden had won the popular vote in Alabama and Mississippi.

The results in the other three states were even more unexpected. After counting had finished, both parties claimed victory in those states. On election night, Tilden was the presumed winner with 184 electoral votes, 19 votes ahead of Hayes and 1 vote away from holding a majority.

The 20 electoral votes of these states (plus Oregon) remained undecided for months as first the two parties and then the two houses of Congress launched separate investigations. Democrats and the Democratic-controlled House committee accused the Republicans of ballot stuffing and coercion. Republicans and the Republican-controlled Senate committee accused the Democrats of the same.

In the end, the presidential election was decided behind closed doors. In what came to be called the Compromise of 1877, the Democrats conceded the remaining electoral votes to the Republicans, making Rutherford Hayes our 19th president, but in return, federal troops were to be removed from the South, essentially ending Reconstruction and returning power to the same men who had controlled the South during the Civil War.

Though violent intimidation at the polls certainly continued, Southern officials found new ways to suppress the Black vote, including Jim Crow laws and grandfather clauses. Bulldosing took on the wider meaning of “to coerce or restrain by use of force,” and it was ripe for a more literal use when large, seemingly unstoppable machines came on the scene.

Thanks to the excellent sleuthing of my cousin Shawn Taylor, I was able to find evidence that these intimidation tactics hit home. On Nov 11, 2020, Shawn alerted me of the following gem she found on GenealogyBank.comthat mentions our 3rd & 4th great-grandfathers, Sheppard and Bob Williams, respectively, as well as Jim Lee, Bob’s son-in-law. They were witnesses to a large group of men, known as “Regulators” and “White Leaguers” hunting down a man named Henry Temple (also believed to be a relative), a member of the police jury in Laurel Hill, Louisiana (West Feliciana Parish).

|

| Image 1 – New Orleans Republican article dated 13 Sep 1876 |

In the state of Louisiana, parishes are synonymous with counties in other states. Police juries are the legislative and executive governing bodies of the parish which are elected by the voters. Additionally, police jurors elect a president of the police jury who serves as the head of the parish government. Police Juries can range in size, depending on the population size. They are common in rural areas and operate as commissions or councils that govern the areas. Obviously, the newly freed people were becoming aware of their rights as citizens of the United States, thus, they organized to improve their living conditions and take control of their communities. A police jury’s duties include, but are not limited to:

- Enacting ordinances and setting policies

- Overseeing budgets and improvement programs

- Holding monthly meetings to address issues and concerns in the community

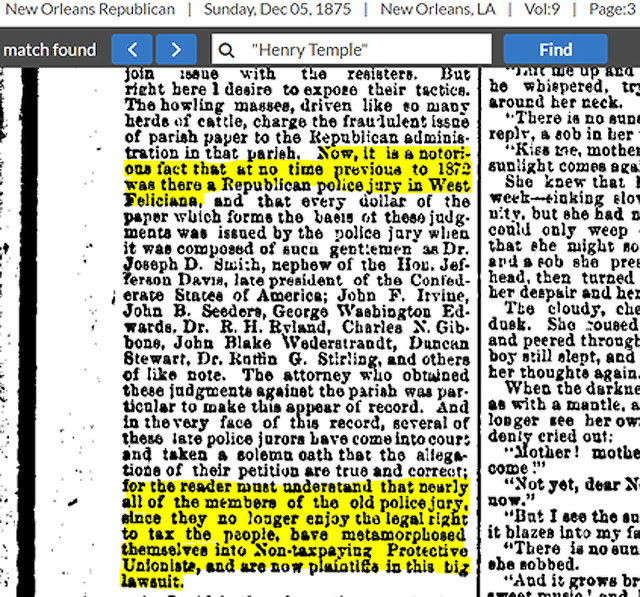

Why the vitriol and violence? What did Henry Temple do? It turns out that since the police jury was under republican control as early as 1872, they began to levy taxes upon the local white citizens who rebuffed the judgements; they even went as far as calling them “illegal” and “fraudulent.” However, in the not-so-distant past, this police jury, when controlled by white democrats, levied similar taxes as this newspaper article from the New Orleans Republic illustrates:

|

| Image 2 |

These “Non-taxpaying Unionist” created an organization known as the “Taxpayers Protective Union” designed to fight these judgements, but their methods show that their organization was really a front for the White Leaguers to actively engage in violence, voter intimidation tactics, and use local government issues to justify their actions. Consequently, their tactics worked–forcing all the black police jurors to resign, so the White Leaguers could appoint their own.

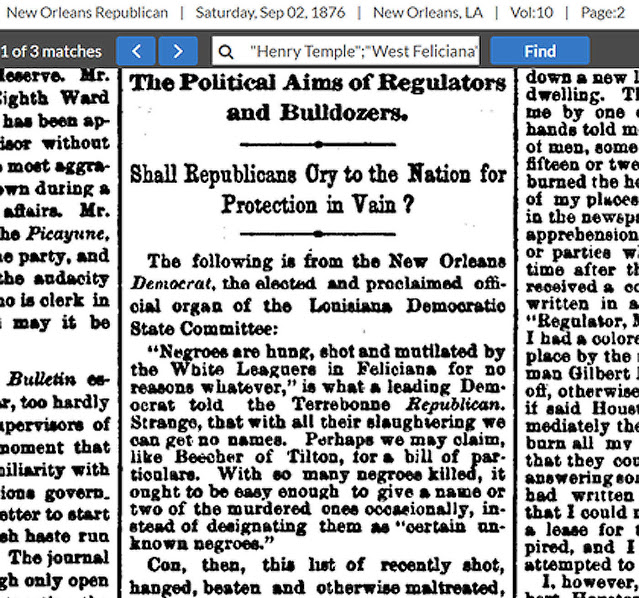

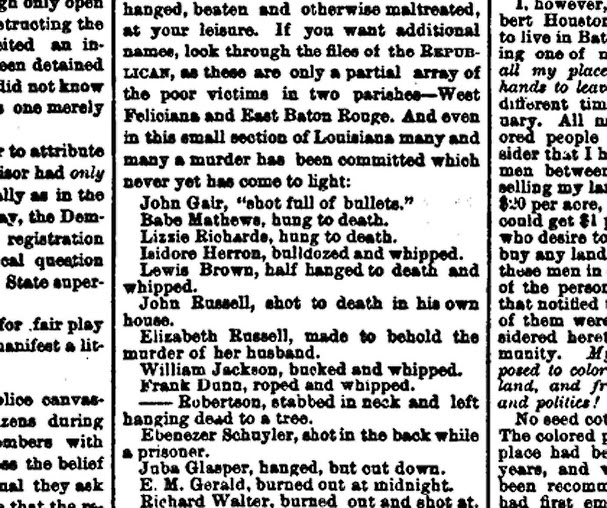

Ten months later, the New Orleans Republic publishes a report from the New Orleans Democrat detailing the names of the black victims terrorized by the White Leaguers in West Feliciana Parish:

|

| Image 3 |

|

| Image 4 |

|

| Image 5 – Louis Morgan, brother of my 3rd great-grandmother, Martha Morgan Taylor |

|

| Image 6 |

|

| Image 7 |

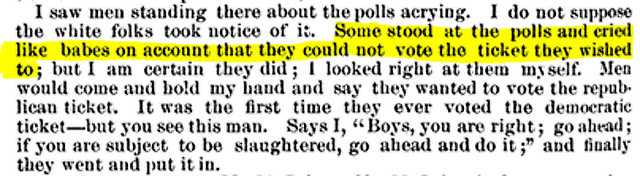

As Shawn and I continued to search these historical newspaper articles throughout the night, my curiosity got the better of me, so I decided to check the “Report of Committees of the Senate of the United States for the 2nd Session of the 44th Congress, 1876-77” on Google Books. I told Shawn that there must be court testimonies of these events because the newspaper articles referenced them. Report No. 701 on Louisiana in 1876 (Vol. 3) entitled the “Reportof the Sub-Committee of the Committee on Privileges and Elections of the UnitedStates Senate,” contains hundreds of testimonies from individuals within the community familiar with the events in question. I found several references to my family members and even their personal accounts. It is not only evident that many African Americans in the parish were intimidated into switching their votes to the democratic ticket, but also that witness tampering and intimation occurred. Many of the black citizens were scared to tell the truth about what they witnessed, heard and experienced; many of their testimonies conflicted with one another and many of them denied observing any acts of violence or intimidation. In some cases, some of them stated they, and everyone they knew, voted the democratic ticket of their own free will which was clearly not true.

There were others who seemed to have little to no fear about telling the truth such as my 3rdgreat-grandmother’s brother, James Morgan who provided testimony in New Orleans on January 13, 1877. His testimony really gave me a sense of the pressure these black citizens were under, and the sentiment of those who, although they were loyal to the “party that gave them their liberty,” realized that survival was the highest priority:

|

| Image 8 – Testimony of James Morgan |

|

| Image 9 – Testimony of James Morgan |

|

| Image 10 – Testimony of James Morgan |

|

| Image 11 – Testimony of James Morgan |

There are some that may find the facts presented in this article as offensive and that is OK—you are entitled to your opinion, as our democracy allegedly guarantees that entitlement. As a result, this article may not appeal to you. This article is written for those seeking the truth about the pillars of this democracy; whether those pillars are reinforced to be self-evident, or if the assumptions about democracy have not guaranteed a path to the desire conclusion. With the voter suppression tactics of today and yesteryear, it begs the question “IS your right to choose guaranteed, let alone, valued and respected?” This article is written for those who are not afraid to put their country to the test and entertain that question.

I’m just a guy telling his family’s true story of how democracy showed up in their lives–generation after generation. From Reconstruction to Jim Crow, to the Voting Rights Act 100 years later which finally guaranteed the right to vote for African Americans, to now–nothing is new under the sun, but when there is, I think we all, regardless of skin color, will enjoy the warmth of it shining on our face.

Freedmen, Firearms, Citizenship and the Right to Assembly

A few years ago, while researching the Freedmen’s Bureau Records, I came across a fascinating report of an incident in Laurel Hill, Louisiana located in West Feliciana Parish. Many of my ancestors were enslaved there and many descendants remained in the parish until the 1950’s.

On July 27, 1867, local white citizens were alarmed over a certain “assembly of the Negroes” in the community. This event which took place every morning, appeared to include some kind of “militarized” exercise causing the local white citizens great fear that they may be in danger.

Below are screen shots of the initial report. Additionally, I followed up with a transcription of the report for ease of read. I labeled illegible letters and words with “(?).”

|

| Image 1 |

|

| Image 2 |

|

| Image 3 |

|

| Image 4 |

|

| Page 1 |

| Page 2 |

|

| Page 3 |

|

| Page 4 |

|

| Page 5 |

| Page 6 |

|

| Page 7 |

|

| Page 8 |

| Page 9 |

David H. Schenk, “Freedmen with Firearms: White Terrorism and Black Disarmament During Reconstruction,” The Gettysburg College Journal of the Civil War Era, Volume 4, Article 4: (April 2014), 7-44; (https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1027&context=gcjcwe: accessed 24 Jul 2020)

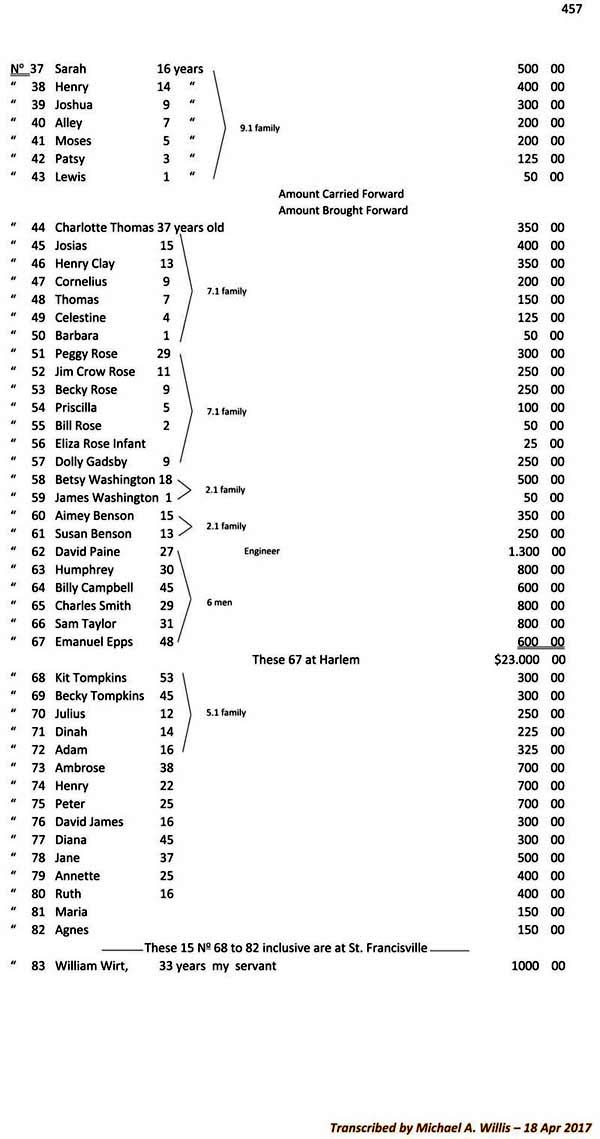

The Wederstrandt Slaves of Harlem Plantation (Plaquemine & West Feliciana Parishes)

In October of 2016, I visited the West Feliciana Parish Courthouse and discovered my 4th great-grandmother, Antoinette “Annette” King, listed as a slave in the inventory of John C. Wederstrandt, owner of Harlem Plantation. The inventory is apart of his Last Will & Testament recorded in Notarial Book K (1849-1853), pages 451-458.

DNA Strikes Again with MORE Descendants of Robert Williams: Yolanda Adebiyi

This past September, I called my cousin, Patricia Bayonne-Johnson, and thanked her for encouraging me to create this blog. She stressed the importance of “telling your story” because of the impact it has, not only on your family members and future generations, but other genealogists as well. In addition, she felt it was important that I “get all these facts, knowledge and experiences out of my head and on paper.” Well, this blog has served all of those purposes, but what I did not expect was for it to find additional family members.

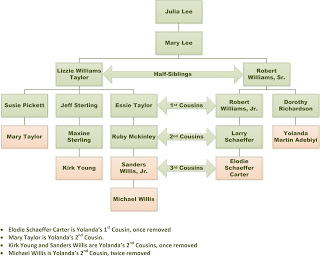

On June 3, 2015, I posted a blog entitled “Another DNA Discovery: The Descendants of Robert Williams – Grandson of Julia Lee” which detailed finding my 3rd cousin, once removed, Elodie Carter, the great-granddaughter of Robert Williams, Sr. Robert was the half-brother of my paternal 2nd great-grandmother, Lizzie Taylor, on their mother’s side. Their mother was Mary (Lee) Williams, the daughter of Julie Lee, a slave from Laurel Hill Plantation in West Feliciana Parish, Louisiana.

|

| Death Notice for Gertrude Williams |

|

| Obituary for Gertrude Williams |

A woman named Yolanda Adebiyi read my post and decided to take a DNA test through 23andme.

You have to ask yourself: why would my blog provoke Yolanda to take a DNA test?

Before she died, Dorothy, Yolanda’s mother, told her that she found out at a young age that her real father’s name was Robert Williams. He was an older man when Dorothy was born. Unfortunately, she only met him a few times before he died and she did not know much about him other than the fact that she had older half-siblings from his previous marriage. After her mother’s death, Yolanda was doubtful she would learn anymore details about the life of Robert Williams, however when she read my blog, she recognized many names I mentioned in the Williams family. Dorothy had an older half-sister named Gertrude Williams, a person mentioned in my blog, that passed away in 2000. Dorothy had a copy of the newspaper death notice from the New Orleans Times Picayune. Yolanda, compared the names with my blog and noticed many similarities. At that moment, she believed she was related to Elodie and I.

On August 25, 2016, Yolanda contacted Elodie via 23andme after she received her DNA results and stated the following:

“Hi Elodie. My name is Yolanda and according to 23andme we are 3rd cousins. I read your blog several months ago and decided to have a DNA test. Glad I did! Robert Wms., Sr. was my mother’s father. I’ve been looking for my mom’s family for years. Would love to connect with you and discover how we are related. Looking forward to hearing from you.”

Elodie forwarded this message to me immediately. I checked my email and discovered a similar message from Yolanda. Elodie spoke to her on the phone, gave her my number and told her to call me immediately. When I received the call, I noticed Yolanda’s area code was from the same location I was born and raised in Northern California. I asked her where she lived. It turned out she was less than 20 minutes from my father’s house (her cousin)!!!! In addition she graduated from the same high school my mother did–one year prior!!!

I was completely shocked and amazed. I logged into 23andme and she was one of the highest matches for several of my paternal relatives. I was even more amazed when she told me the story of how she came to find out about us. The pedigree chart (below) diagrams some of the descendants that tested with 23andme. Please note: this chart does not represent all the descendants of Julia and Mary Lee.

|

| The DNA Descendants of Mary Lee |

I told her that I am a member of the African American Genealogical Society of Northern California (AAGSNC) and that I attend the monthly meetings. I invited her to come so that my father and I could meet her. She told me she attended previous meetings, but that was a few years prior. We more than likely crossed paths before without knowing we were so closely related! Below is a picture from AAGSNC’s 20th Anniversary Celebration taken on September 17, 2016, in which I met Yolanda for the first time:

|

| Michael Willis (L) & Yolanda Adebiyi |

It was a very emotional meeting to say the least.😊

|

| Yolanda’s DNA Segment Comparisons to other Family Members |

Talk About Twists And Turns And Crumbling Brick Walls: DNA Confirms My Penny Lineage

Before I get started here’s a brief look at my paternal family tree for the reader’s benefit of understanding this article.

In August of 2015, I wrote a blog about ending my 9 year search for my 2nd great-grandmother’s maiden name, Mamie (Penny) Benton. In the months that followed, I’d spent some time researching her family tree and I came across some possibilities, but I had no direct evidence to support my theories. Since her death certificate did not have her parents names listed, I tried studying census records looking for families with the surname PENNY living in Gramercy, Louisiana in (St. James Parish) as well as Baton Rouge, Louisiana.

According to her death certificate, Mamie died in Gramercy at the age of 38 in 1917. My late great aunt, Marguerite (Jackson) Vernell, told me that her mother, my great-grandmother, Artimease Benton, and her siblings, all the children of Mamie Penny and Edward Benton, were born in St. James Parish so I assumed that Mamie’s family was from that parish. Unfortunately, all my search attempts turned up empty so I set my sights on studying Penny families in Baton Rouge. In addition, I realized I failed to take into account that “Mamie” was potentially a nickname used in place of “Mary.”

That’s when my fortunes changed.

Since Mamie was born around 1878 according to her death certificate, I started looking for “Mary Pennys” born within a five year time frame and I had two hits: One Mary Penny, born in 1876, living in East Baton Rouge Parish on the 1880 US Federal Census and the other was born in April of 1877 living in the same Parish in 1900. Fortunately, both hits were the same woman in the same households:

1880 US Federal Census – East Baton Rouge Parish, 1st Ward, Enumeration District 103

Head of Household: Jack Penny; age 44; Birthplace: Missouri.

Wife: Maria Penny; age 29; Birthplace: Alabama.

Son: David Penny; age 8

Daughter: Mary Penny; age 4

Daughter: Luella Penny; age 4

– Jack states his father was born in Africa and his mother was born in Tennessee

– Maria states both parents were born in Georgia

– All their children were born in Louisiana

1900 US Federal Census – East Baton Rouge Parish, 1st Ward, Enumeration District 27

Head of Household: Jack Penny; age 59; Birthplace: Missouri.

Wife: Marie Penny; age 46; Birthplace: Alabama

Son: David Penny; age 28

Daughter: Mary Penny; age 23

Daughter: Ella Penny; age 19

Daughter: Else Penny; age 18

Daughter: Odeal Penny; age 13

Son: James Penny; 8 months

– Jack states both parents were born in Missouri

I also tracked this family in 1870 and discovered “Jackson & Maria Penny,” ages 36 and 22 respectively, living in St. James Parish during enumeration. There were no kids listed. Both were also born in Missouri and Alabama, respectively. Lastly, I obtained Maria Penny’s death certificate under the name “Mariah” Penny. It listed her as the widow of Jack Penny. It also stated that she was born in Macon County, Alabama and born to Sam and Della GREEN. The informant was “Della Harris” who I presumed was her daughter, “Odeal,” but I wasn’t sure.

I had a strong hunch these were the Penny’s I was looking for but without stronger circumstantial evidence I couldn’t draw that conclusion so I shelved this project for a while and move on to other things.

Then, something happened that I never expected…

At the end of 2015, I had a conversation with my cousin, Carol Simmons, about taking a DNA test. I was telling her how awesome and interesting this journey has been tracing ancestry through DNA and so I suggested that she try it. Referring back to my pedigree chart at the top of this post, my great-grandfather was Emanuel Willis, Jr. Carol Simmons is the grandchild of Emanuel’s older sister, Irene (Willis) Simmons. My hope was that Carol’s DNA would add to the growing list of Willis relatives that contributed DNA samples furthering my research on the Willis line. She contacted me in the summer of 2016 to let me know that she took the test and her results were in. I couldn’t wait to login and see how she compared with the other Willis relatives, but what I found out was that she not only matched my father, his paternal uncle Edward Willis, myself and cousins who descended from Willis’, but she also matched my great aunt, Marguerite (Jackson) Vernell. The startling thing about this fact was that Marguerite is my grandfather’s half-sister on their mother’s side.

My great-grandmother, Artimease Benton, married Emanuel Willis and from this union four children were born:

- Sanders Willis Sr, my grandfather

- Brenetta Willis

- Ruth Willis

- Edward Willis

Emanuel died at the age of 28. Some years later, Artimease married her 2nd husband named Will Jackson and from that union, one child was born: my Aunt Marguerite (Jackson) Vernell, therefore, Aunt Marguerite is not a Willis. How in the world could Carol Simmons, a descendant of Willis’ match my Aunt Marguerite who is not the daughter of a Willis?

|

| Carol’s Matching Segments with Willis Descendants and Marguerite Vernell |

I called Carol as soon as I became aware of this information and I immediately started asking her questions about other branches of her family tree. I discovered that her mother, Delores (Coates) Simmons was the daughter of a woman whose maiden name was Margareat PENNY. Margareat Penny was the daughter of David Penny, the oldest child of “Mariah” Penny–according to oral family history (as told by Margareat Penny). No one ever mention the name Jack Penny so Carol was unfamiliar with him, but her family was familiar with “Aunt Della Harris” – the same person named “Odeal” on the 1900 census!

As crazy as it sounds, this is how I confirmed my relationship to Jack and Mariah Penny–they were, in fact, my 3rd great-grandparents.

From Slave to Soldier: Jackson Penny

|

| Jack Penny’s Certificate of Promotion |

The card indicates that Jack initially served in Company G, 8th Regiment of the Corp d’Afrique, the first militia of African Americans organized from the Louisiana Native Guard to truly serve as combat soldiers in the Civil War and not just as war laborers. The 8th Regiment of the Corp d’Afrique, which fought and won major battle at Port Hudson, Louisiana, was later reorganized into the 80th Regiment of the USCT. By the end of Jack’s service, he was promoted from Private to Corporal, then from Corporal to Sergeant.

|

| Jack Penny’s Discharge Papers |

I ordered the widow’s pension Mariah filed in 1902 after Jack’s death from the National Archives in Washington, DC and discovered a tremendous amount of genealogical information in her file. In a firsthand account during her deposition, Mariah corroberates the information in her death certificate–that her maiden name is GREEN and that she was born in Macon County, Alabama. She states her family were the slaves of “Russ Bridges” and that her parents “took her to Texas for safe keeping” when the war broke. They lived six miles from Marshall, Texas where she was “hired out by a man in Jonesville named ‘Lang’ who was a furniture dealer.” It was during this time she met Jack Penny on the train going from Jonesville to Marshall, Texas and stated that “he fell in love with me at once, and he began writing to me afterwards, but we got engaged on the train.” They were later married at the home of “Arch Penny,” Jack’s brother who later moves to Champaign, Illinois with his family and takes their mother, Elsie Penny, with them.

Unlock with Patreon

Unlock with Patreon